The Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction under §199A lets you deduct up to 20% of your S‑Corporation profits. It can be one of the most valuable tax breaks if you structure your compensation correctly. Your salary directly affects how much of the QBI deduction you keep — pay yourself too little, and you risk losing it entirely; pay too much, and you give up unnecessary payroll tax savings.

As an S‑Corp owner, you face a balancing act. The IRS requires “reasonable compensation,” but the definition of reasonable depends on your industry, duties, and profit level. Too many business owners default to the lowest possible wage to minimize payroll taxes, not realizing this move can shrink or remove their QBI deduction altogether.

In this article, you’ll see how the Section 199A deduction works, what reasonable compensation really means, and how wages can both reduce and increase your QBI benefit. Nguyen & Associates, CPA, Inc. breaks down practical salary strategies, provides a step‑by‑step method to find your target pay range, and shows common mistakes that cost S‑Corp owners thousands in lost deductions.

What The QBI Deduction Covers

The Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction reduces how much of your business income gets taxed. It allows certain small business owners to deduct a portion of their profits based on how their income is structured and how the IRS defines qualified business income.

Quick Definition Of §199A

The §199A deduction, created by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, gives owners of pass-through entities—such as S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships—a deduction of up to 20% of their qualified business income. This income must come from a U.S. trade or business and exclude several types of investment and wage income.

You don’t reduce taxable income directly by 20%. Instead, the deduction applies after calculating your qualified business income, subject to rules and limitations. At high income levels, the deduction may be capped by W-2 wages or the value of qualified property owned by the business.

Income that qualifies must come from active business operations, not from dividends, capital gains, or interest. For example, if your S corporation earns $150,000 after paying reasonable compensation, that $150,000 may be eligible for the deduction—up to $30,000 depending on other factors.

The deduction applies only to income “effectively connected” with a U.S. trade or business. It doesn’t apply to foreign income or certain specified services when income exceeds set thresholds.

Which S-Corp Income Qualifies

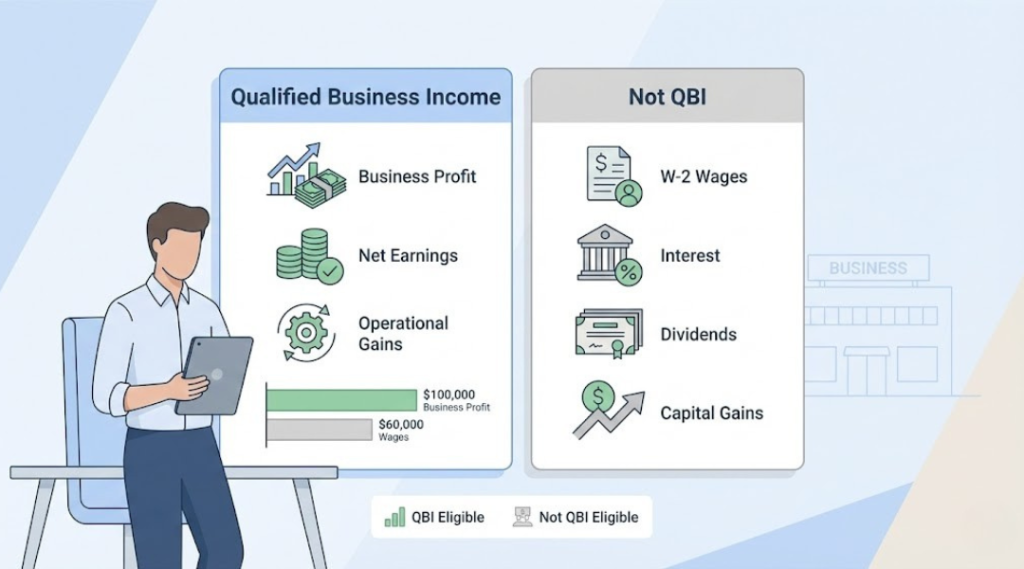

In an S corporation, the QBI deduction applies to your share of business profits, not to wages you pay yourself as the owner. The salary you take counts as reasonable compensation and is excluded from qualified business income under IRS rules.

Your qualified business income typically includes:

- Net earnings from your company after subtracting ordinary expenses

- Profits passed through to you as an owner, not paid as W-2 wages

- Gains and losses from normal business operations

The IRS excludes reasonable compensation, capital gains, dividends, interest income, and income earned outside the U.S. This means only the business’s operating profit counts toward the deduction.

If your S-corp has $100,000 in profit and $60,000 in wages, only the $100,000 may qualify as QBI. That amount could give you up to a $20,000 deduction before applying any wage or property limits. Keeping detailed records and verifying that your salary is reasonable helps ensure compliance and maximizes your eligible deduction.

What Reasonable Compensation Means

Your reasonable compensation is the amount you, as an S‑Corp owner-employee, must pay yourself for the services you perform before taking any profit distributions. The IRS reviews this closely because it affects both employment taxes and your eligible Qualified Business Income (QBI) for the §199A deduction. Paying yourself fairly helps you stay compliant and protect your deduction.

IRS Standards And Common Benchmarks

The IRS defines reasonable compensation as what a business would pay an employee for similar work under comparable conditions. The agency examines your role, hours, skills, and business profits to determine fairness.

Courts and tax professionals often rely on three main methods:

| Method | Description | Common Use |

|---|---|---|

| Cost (Many Hats) | Breaks down multiple duties and assigns market pay to each. | Solo owners performing varied tasks |

| Market Approach | Compares wages to similar roles in the same industry. | Most relied upon by courts |

| Income Approach | Tests whether your pay leaves a fair return for hypothetical investors. | Used when ownership and capital investment are major factors |

A practical benchmark is to set your pay around 60–70% of what you’d earn doing similar work as an employee elsewhere. Factors like company size, location, and experience still matter. Documenting your process with salary data, time logs, and job descriptions helps defend your position if audited.

Why Wages Must Be Separated From QBI

Your W‑2 wages from the S‑Corp do not count as Qualified Business Income. Only the remaining business profit after paying yourself a reasonable salary qualifies for the §199A deduction. This rule prevents owners from underpaying wages simply to increase their deduction.

For Specified Service Trades or Businesses (SSTBs)—such as health, legal, or financial services—the QBI deduction phases out as income rises. Paying proper wages keeps your structure compliant and your deduction accurate.

Separating wages and QBI also supports benefits like retirement plan contributions and health insurance deductions for 2% shareholders. Treating compensation and profit as distinct categories ensures your returns match IRS expectations and avoids penalties tied to misclassification.

How Wages Reduce Or Increase The QBI Deduction

Your QBI deduction depends heavily on how much you pay yourself in W-2 wages. The amount of wages affects not only payroll taxes but also how much of your business income qualifies for the §199A deduction, especially once your taxable income exceeds certain thresholds.

Relationship Between Shareholder Wages And QBI Amount

As an S‑Corp owner, your QBI deduction comes from the portion of business profits that remain after paying yourself a reasonable salary. If you pay yourself too little, the IRS may deny part of the deduction or reclassify distributions as wages. If you pay too much, the higher payroll taxes can erase some of the savings from the deduction.

When your taxable income rises above the phase‑in range, the deduction becomes limited by one of two formulas:

| Limitation Test | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 50% of W‑2 wages | Your deduction cannot exceed half of the wages paid by the S‑Corp. |

| 25% of W‑2 wages + 2.5% of qualified property (UBIA) | Useful when your business owns substantial assets like real estate or equipment. |

Your salary level determines how much income qualifies for the 20% deduction. Proper planning balances wages high enough to meet these tests but low enough to minimize payroll and Medicare taxes.

How Wage Levels Affect The 20 Percent Calculation

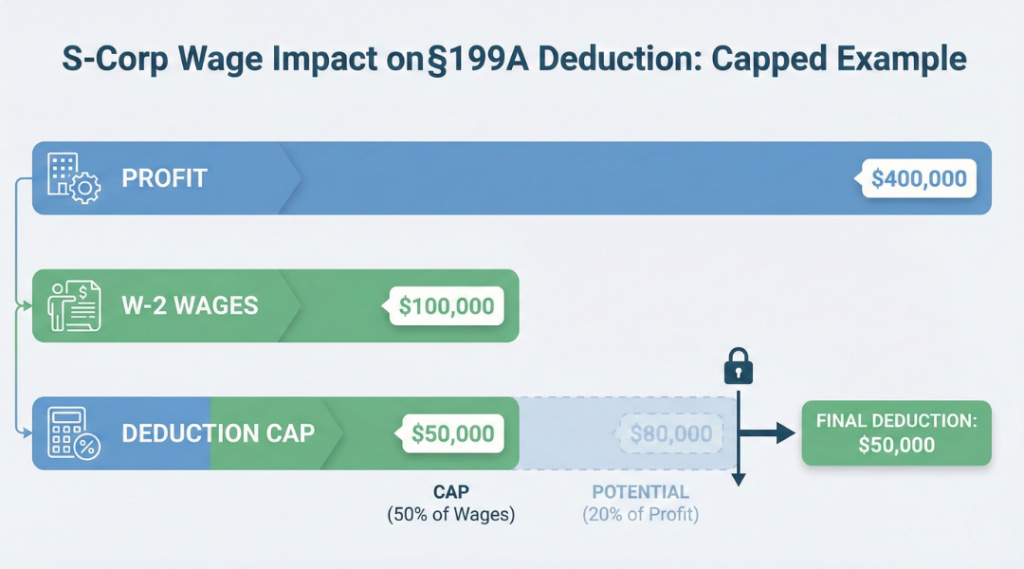

The general deduction under §199A equals 20% of qualified business income, but it can shrink once your taxable income surpasses the IRS income limitation for your filing status. At lower incomes, this limit does not apply, so you receive the full benefit regardless of wage levels.

At higher incomes, W‑2 wages directly cap the deduction. For example, if your S‑Corp reports $400,000 in profit but pays only $100,000 in wages, the deduction is limited to $50,000 (50% × $100,000) even though 20% of profits would be $80,000. Increasing wages raises the wage cap but reduces QBI since wages are deducted from profit.

This trade‑off means modeling different salary levels is essential. The “sweet spot” usually occurs where wages meet the minimum needed to unlock the full 20% deduction under the wage test, while keeping total tax and payroll costs as low as possible.

Finding The Right Balance: Not Too High, Not Too Low

Your salary from an S-Corp must fall within a range that satisfies IRS standards while keeping your tax benefits intact. Paying too much or too little affects your Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction, payroll taxes, and compliance risk.

Problems With Overpaying Wages

Setting your W-2 wage too high increases Social Security and Medicare taxes without giving you any extra QBI deduction benefit. The QBI deduction under §199A applies only to the business’s qualified profits, not to your wages. Every dollar of additional salary reduces your pass-through income and therefore reduces the base used to calculate the 20% deduction.

For example:

| Salary | Pass-Through Profit | Potential QBI Deduction (20%) |

|---|---|---|

| $200,000 | $300,000 | $60,000 |

| $250,000 | $250,000 | $50,000 |

As wages climb, your QBI base shrinks. You might still qualify for the standard deduction or itemized deductions on your return, but those apply separately and don’t offset this specific loss.

You also pay the employer portion of payroll taxes that never apply to S-Corp distributions. Overpaying makes it harder to maintain liquidity and can reduce retirement contribution flexibility if cash flow tightens.

Risks Of Underpaying Wages And IRS Scrutiny

Paying yourself too little can create serious problems. The IRS requires S-Corp shareholders who actively work in the business to take a “reasonable salary.” If your pay appears too low compared to industry norms, auditors may reclassify part of your distributions as wages. This leads to back payroll taxes, penalties, and interest.

Too little salary can also limit your QBI deduction at higher income levels. When your taxable income exceeds the §199A phaseout thresholds, the deduction depends on W-2 wages and depreciable property. If your business has no other employees, low wages can reduce or entirely remove your QBI benefit.

A below-market wage further restricts your retirement plan contributions, because S-Corp profits are not treated as earned income. That means smaller 401(k) deferrals and missed long-term tax savings, even after factoring in the standard or itemized deductions you might claim personally.

Step-By-Step Method To Determine A Reasonable Compensation Range

You need a pay figure that reflects the fair market value of your work while still supporting your tax strategy. To do this, evaluate measurable factors about your role and use reliable compensation data that aligns with your business profile.

Factors To Review (Role, Industry, Location, Experience)

Start with your role and duties. The more time you spend managing daily operations or performing high-skill tasks, the higher your pay should be. Document your job functions clearly—administration, sales, or production—and note the percentage of work each category represents.

Industry type also matters. For example, engineering firms or medical practices usually show higher median wages than consulting or design businesses. Comparing your business activity to others in the same sector helps you stay within IRS expectations for “reasonable.”

Consider your business’s location. Salaries in large metro areas often exceed those in rural markets due to cost-of-living differences. Use regional pay data or Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports to match your area’s wage range.

Experience and credentials complete the picture. Owners with specialized certifications, long tenure, or advanced degrees can justify higher pay levels. Align your expertise with what a third party would likely pay someone to perform the same work.

Using Comparable Wage Data Effectively

Once you identify the key factors, use data sources that show credible wage information. BLS, salary.com, and industry association reports all provide median and percentile ranges by occupation. Choose benchmarks that align with your job duties, not your ownership status.

Create a simple table comparing different data points:

| Source | Median Wage | 75th Percentile | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLS Data | $92,000 | $110,000 | National average |

| Industry Survey | $95,000 | $120,000 | Regional sample |

| CPA Study | $100,000 | $125,000 | Owner-operated businesses |

Use these results to form a pay range, then adjust for hours worked and company profit level. If you split time between services and management, assign partial value to each. Document calculations and references, because supporting evidence helps if the IRS reviews your compensation later.

Short Numerical Example

A small change in how you set your S-Corp salary can affect your Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction under §199A. The numbers below show how choosing a reasonable salary influences both your deduction and your total tax cost.

Showing How Compensation Changes The Final §199A Deduction

Assume your S-Corp earns $200,000 in net profit before salary. You pay yourself a $60,000 W-2 salary, leaving $140,000 of pass-through profit. Your QBI deduction equals 20% of that profit, or $28,000.

Now imagine you lower your salary to $40,000. Your profit rises to $160,000, but if your total income exceeds the threshold, the IRS wage limitation rule may cap your deduction at 50% of wages, or $20,000.

| Scenario | W-2 Salary | Pass-Through Profit | QBI Deduction (20%) | Wage Limit (50% of W-2) | Allowed Deduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | $60,000 | $140,000 | $28,000 | $30,000 | $28,000 |

| B | $40,000 | $160,000 | $32,000 | $20,000 | $20,000 |

When preparing your tax return, both deductions appear before computing taxable income, but the allowed amount changes depending on how “reasonable” your compensation is under IRS standards. A balanced salary often yields the most efficient mix of payroll tax cost and §199A savings.

Common Mistakes And How To Avoid Them

Many S-Corp owners lose part of their Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction because they miscalculate the balance between salary and business profit. Others fail to prove that their compensation meets IRS standards for “reasonable pay,” leaving them vulnerable to audits and lost deductions.

Overlooking Wage-To-QBI Ratios

Your QBI deduction depends not only on profit but also on how much you pay yourself in W-2 wages. If you pay too little, your deduction can drop to zero once your income exceeds the QBI phase-out range. Paying too much, however, increases payroll taxes and reduces pass-through profit.

Stay aware of the 50% wage limitation rule. The deduction for high earners cannot exceed 50% of your total W-2 wages or 25% of wages plus 2.5% of depreciable property value. For most S-Corps without major assets, wages play the deciding role.

To avoid this mistake:

- Model different salary levels before finalizing payroll.

- Review your expected taxable income to see if you’re near phase-out thresholds.

- Adjust compensation annually to match business growth.

Using a simple ratio table can help track performance:

| Metric | Target Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| W-2 Wages ÷ Business Profit | 0.25–0.40 | Often optimal for non-asset-intensive firms |

| QBI Deduction ÷ Taxable Income | ~15–20% | Typical for balanced setups |

Ignoring Industry Benchmarks Or Documentation

You must show the IRS that your salary is “reasonable” compared to what someone else would earn for similar work. Problems arise when owners choose arbitrary pay without supporting data. The IRS reviews factors such as job duties, training, hours worked, and business size.

To avoid issues, gather clear proof:

- Use industry wage surveys (for example, Bureau of Labor Statistics data).

- Keep ** written job descriptions and timesheets** showing how you contribute value.

- Compare your compensation to roles with similar revenue or staff size.

If you underpay yourself, the IRS may reclassify distributions as wages and assess back payroll taxes plus penalties. Paying a documented, defensible salary protects your QBI deduction and reduces the risk of reclassification during an audit.